Raising Expectations (and Raising Hell)

The Death and Life of the Great American School System

The Prosecution of George W. Bush for Murder

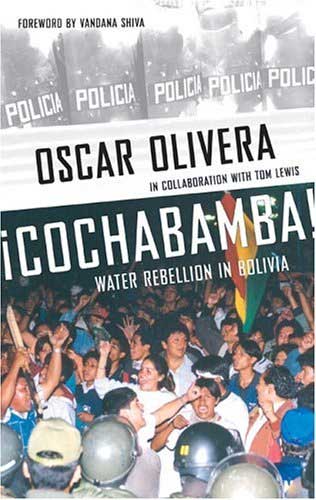

Dissent: Voices of Conscience Medical Apartheid and The Ethnic Cleansing of PalestineA Century of Media, A Century of War The Bush Agenda Cochabamba! Confessions of an Economic Hitman The Exception to the Rulers The Weapons of Mass Deception

In its scope, its detail, its analysis, and in its inspiring simplicity, this is a superb book. It tells the captivating story of the “water wars”, the valiant struggle fought and won by the people of the Bolivian city Cochabamba to roll back the privatization of the city’s water supply which would have further impoverished an already suffering population and added to the indignity of their lives while allowing the Bechtel Corporation and its subsidiaries unprecedented control of this vital resource. Oscar Olivera, the spokesperson for the Coordinadora, the organization that succeeded in bringing together thousands of Bolivians from all walks of life to mount one of the largest and most dynamic protest movements in recent history, tells his story to translator Tom Lewis. What emerges is a well paced narrative of true heroism and idealism that keeps the reader as engaged as with any novel, and yet it is packed with information. The story begins in 1999.

In its scope, its detail, its analysis, and in its inspiring simplicity, this is a superb book. It tells the captivating story of the “water wars”, the valiant struggle fought and won by the people of the Bolivian city Cochabamba to roll back the privatization of the city’s water supply which would have further impoverished an already suffering population and added to the indignity of their lives while allowing the Bechtel Corporation and its subsidiaries unprecedented control of this vital resource. Oscar Olivera, the spokesperson for the Coordinadora, the organization that succeeded in bringing together thousands of Bolivians from all walks of life to mount one of the largest and most dynamic protest movements in recent history, tells his story to translator Tom Lewis. What emerges is a well paced narrative of true heroism and idealism that keeps the reader as engaged as with any novel, and yet it is packed with information. The story begins in 1999.

“In June 1999, the World Bank issued a report on Bolivia discussing the water situation in Cochabamba. The World Bank, which along with the International Development Bank had made privatization a condition for loans, recommended that there be “no public subsidies” to hold down increases in the price of water service. ........ A key component of the government’s effort to privatize water was the October 1999 promulgation of Law 2029 which governed drinking water and sanitation”. (pg. 8)

This extraordinary Law 2029 not only wiped out centuries old indigenous customs of collective water use but had provisions which were shocking in their scope. Bechtel was granted an exclusive monopoly on water distribution to the extent that even personal private wells were now prohibited. And if that weren’t enough, the people were not even permitted to collect rain water! And no matter what happened Bechtel was guaranteed by the State to make at least a 16% yearly profit. Call it what you will but this cannot be defended in the name of capitalism or neo-liberal free markets. This is high tech corporate feudalism, or fascism. These are gangsters in suits and ties who use corrupt governments for the facade of legitimacy.

But in February of 2000, thousands of outraged citizens refused the plan and took to the streets under the leadership of the Coordinadora, an umbrella group of grassroots organizations that eventually forced the government to back down from the privatization plan.

In addition to the story of the struggle leading to citizen control over the water system, the book is amplified with various interviews and articles by other authors who discuss the various dimensions of popular resistance to globalization in Latin America. Historical context is provided along with an analysis of the problems and obstacles faced. New grassroots forms of participatory democracy are discussed with possible future strategies and solutions envisioned. As Racquel Gutierrez- Aguilar aptly says in her commentary:

“.............Cochabamba raised two fundamentally political questions: Who owns basic resources? And in what form should such resources be managed? (pg. 53)

These are in fact fundamental questions and their resolution is far from being realized. The struggle in Latin America, and indeed all across the Third World continues. It is a struggle to come to grips with the bitter poverty afflicting a majority of the world’s people. Local solutions in conflict with solutions proposed by those professionals living thousands of miles away comfortably insulated from the “reality on the ground”, is just one of the tensions dramatized in Cochabamba. Globalization is a story in progress. This excellent volume is just one of its chapters, a most inspiring and instructive chapter. As the contours of econmic development in the Third World unfold, the challenge to social, political and economic orthodoxies will be to abandon rigid dogma and adapt to the needs of indigenous peoples as they themselves define those needs. This is the first lesson of Cochabamba.

Russell Branca

New York