Raising Expectations (and Raising Hell)

The Death and Life of the Great American School System

The Prosecution of George W. Bush for Murder

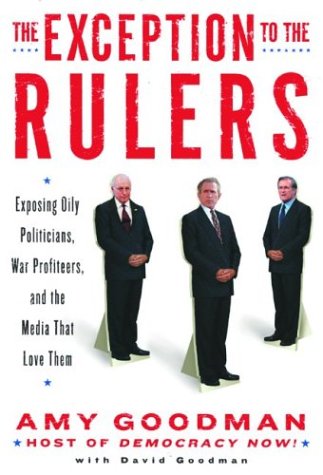

Dissent: Voices of Conscience Medical Apartheid and The Ethnic Cleansing of PalestineA Century of Media, A Century of War The Bush Agenda Cochabamba! Confessions of an Economic Hitman The Exception to the Rulers The Weapons of Mass Deception

With this book Amy Goodman has made her debut as an author. She is the host and executive producer of Democracy Now! the nationally broadcast radio and TV show of news and political analysis which has risen dramatically over the last two years to become the premier media voice from the left. Written with her brother David, himself a distinguished journalist and author, the book is largely a compilation of stories covered on the show over the last few years and so regular listeners will find them familiar. It is not however merely “Democracy Now!’s Greatest Hits”. It is a carefully selected collection of interviews, news stories, and “from the field” reports, all of differing lengths, some no more than two paragraphs, woven together to achieve the goal of the book’s subtitle; that is, to expose the corruption of government policy by politicians, particularly those connected to the oil and defense industries, and above all the corporate media that has failed in its civic duty to challenge them. Not surprisingly it is for the latter that Goodman reserves her most acrid criticism and, as she has done relentlessly time and time again over the years, she argues forcefully and passionately for her signature cause; the call for a media independent of corporate control.

With this book Amy Goodman has made her debut as an author. She is the host and executive producer of Democracy Now! the nationally broadcast radio and TV show of news and political analysis which has risen dramatically over the last two years to become the premier media voice from the left. Written with her brother David, himself a distinguished journalist and author, the book is largely a compilation of stories covered on the show over the last few years and so regular listeners will find them familiar. It is not however merely “Democracy Now!’s Greatest Hits”. It is a carefully selected collection of interviews, news stories, and “from the field” reports, all of differing lengths, some no more than two paragraphs, woven together to achieve the goal of the book’s subtitle; that is, to expose the corruption of government policy by politicians, particularly those connected to the oil and defense industries, and above all the corporate media that has failed in its civic duty to challenge them. Not surprisingly it is for the latter that Goodman reserves her most acrid criticism and, as she has done relentlessly time and time again over the years, she argues forcefully and passionately for her signature cause; the call for a media independent of corporate control.

In the introduction, titled “The Silenced Majority”, we catch a glimpse of how Goodman’s passion for journalism was shaped from personal experience. It begins with an account of her harrowing experience reporting from East Timor on a November day in 1991, a day that saw the brutal massacre of almost 300 innocent villagers by the Indonesian army. It was just one of many countless episodes in the horriffic story of genocide by Indonesia in East Timor that, beginning in the 1970’s resulted in the slaughter of hundreds of thousands of East Timorese in their struggle for independence. Yet in the American press there was a literal blackout and no mention of it was made. Why? Because at the time Indonesia was a US ally and its military was supplied by the US. This goes to the heart of Goodman’s outrage as she advances the idea that the role of a journalist is to “go to where the silence is” or “to give voice to those who are powerless and have no voice”.

The book goes on to chronicle a wide range of anecdotes not usually covered by the mainstream media. The harrassment and abuses visited on the immigrant community in the aftermath of 9/11 provides fertile ground. Yes, here in America there were people who “disappeared”, taken by police into custody without notification to their families who had no information as to their whereabouts and were held without access to legal assistance. The intensification of pressure against anyone who voiced dissent over government policy extended to a Greek professor visiting New York to address an academic conference at NYU. He was handcuffed and interrogated at JFK airport and asked questions like “Are you against the war in Iraq?”. The list goes on, with one example after another of the excesses of the Ashcroft justice department.

As is the custom, the back jacket of a book is reserved for the accolades by notable personalities. Among those chosen for this book is historian Howard Zinn who places Goodman in the great “muckraking” tradition from Upton Sinclair to I. F. Stone. While muckraking is certainly a part of what she does and as a muckraker she is as competent as anyone, I think what Goodman is about is much more. I think that where she is at her best, where she truly excels is in uncovering the hypocrisy that is concealed in normalcy. Nowhere is this more compelling than in her harsh and unyielding attack on the media’s coverage of the war in Iraq. As she says on pg. 206:

“The rules of mainstream journalism are simple: The Republicans and Democrats establish the acceptable boundaries of debate. When those groups agree - which is often - there is simply no debate. That’s why there is such appalling silence around issues of war and peace.”

For Goodman, stretching those boundaries is what makes democracy healthy. The “sanitizing” of the war has been for her one of its great scandals. Corporate media has fulfilled the function of state propaganda as well as any government, democracy or dictatorship, could hope for. There are no victims in this war. Where are the casualties? We bomb incessantly and yet no civilians die, no coffins of American soldiers are permitted on TV, and Bush never attends a funeral. It is all part of an unreal video game designed to insulate the public from the realty of the human cost of war and rationalized in the name of “good taste”. This was what sparked her pointed exchange with CNN’s Aaron Brown. So the networks hire retired generals who dazzle us describing how the fantastic new military technology works. When Goodman asks Frank Sesno of CNN why no peace activists appear to comment he replies that the generals are “analysts and not advocates”. But as Goodman has argued, that is simply not the case. Why then would there be any objection to medical doctors giving an objective analysis of the effects of daisy cutter bombs on the children who pick them up and have their limbs blown off? Because we know that an analysis, no matter how “objective”, is not value neutral when it only describes a portion of the reality, a portion selected by someone who is not neutral. Goodman goes on to criticize the system of “embedded” reporters and contrasts their fate with the “nonembedded” reporters, some of whom became targets of the US military.

Goodman is very skillful at the art of using contrast. One very good example involves the case of Judith Miller, the reporter for the New York Times whose stories supporting the claim that Saddam still had stockpiles of WMD appeared regularly before and after the war. Most all of the claims have now been proven to be fabrications fed to her by the now discredited Ahmed Chalabi. Compare how the Times dealt with her with how they dealt with the Jayson Blair case. Blair, a young inexperienced black reporter admitted to having fed a string of false stories to the Times over a period of a few years. None of these stories had any vital social importance but the Times ran a 5 page 7000 word expose in the paper wallowing in its own self righteous pretensions to integrity. As for Miller, who is white and upper class, nothing happened, no recriminations, no loss of prestige, no apologies, and from the Times, no corrections, just thousands of lives lost. *

The theme of disinformation in the media is explored in more depth in a disturbing chapter called “Psyops Comes Home” . Drawing on retired Air Force Lieutenent Colonel Sam Gardiner’s lengthy study of false stories deliberately or at least carelessly fed to and accepted by the media, Goodman chooses some 20 odd examples to produce a startling effect. The Orwellian nature of these sinister efforts to manipulate public perception of reality in that murky area where private and government actors seem to collaborate in the shadows is quite alarming.

As would be expected Goodman’s career has brought her in contact with the powerful and famous. Since witholding access to these figures is often used against journalists to “keep them in line”, Goodman has drawn a line of her own; “never compromise your integrity for access”. Examples of her upfront style abound with excerpts from exchanges with such luminaries as Newt Gingrich, Charlie Rose, Bob Kerrey, Richard Holbrooke, Aaron Brown, and Tom Brokaw. But my favorite of all is her dialogue with Bill Clinton on election day of 2000. Out of the blue, surprising everyone, Clinton decides to call the station during live on air time, trying to pitch to get out the vote for Al Gore. He evidently expected that the tiny listener supported radio station would just be thrilled to have him on for a few minutes. But Goodman proceeds to drill him with one hard critical question after another, challenging him on his foreign and domestic policies and not letting him up for air.

The Exception To The Rulers is written in a clear, craftsmanlike and unassuming prose style that reflects the value journalism places on concision and focusing on the essential. It flows, and is for the most part an enjoyable read, dotted with plays on words to add levity. But it is deceptive, because when you’re done you’re amazed at just how much information you’ve absorbed. You can read from beginning to end or select portions at random. It’s a great book to keep on the coffee table where it will always be available to stimulate conversation. And all of it is well documented. Particularly refreshing is the little footnote on the use of chemical weapons against the Kurds at Halajba in 1988 which everyone assumes was the work of Saddam. In reality there is credible evidence that it was the Iranians who did it.

Aside from the technicians, a radio/TV news program is made by three different persons: the reporter in the field, the presenter or host on air, and the executive making the editorial and managerial decisions in the background. As far as I know Amy Goodman is unique in that she wears all three hats simultaneously. Now, stretching her own personal boundaries, she can add a fourth hat, that of author.

* Finally, on Wednesday May 26, 2004, just as this review was about to go to press, the New York Times printed a rather lengthy “mea culpa” on page A10 admitting to the fabrications. The Times does not mention Miller by name but rather attributes the problem to collective errors of judgement. They do mention Chalabi, his defectors, and several specific stories.Two of the dates with false stories are mentioned in Goodman’s book and the entire affair was a recurring theme on DNow! for more than a year and a half.

Russell Branca,

New York